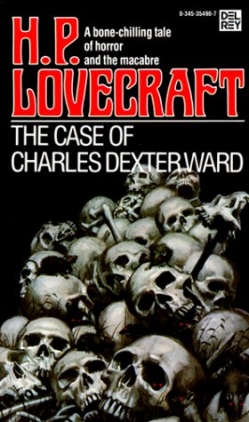

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at the finale of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. CDW was written in 1927, published in abridged form in the May and July 1941 issues of Weird Tales; and published in full in the 1943 collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep. You can read the story here.

Catch our posts on the earlier parts of the story here, here, and here. Spoilers ahead.

Willet and Ward Senior agree at last that they’re in a Mythos story. They seek the crypt beneath CDW’s bungalow, and find entry through a basement platform. Noxious fumes cause Ward Senior to pass out. Willett sends him home, breaking the first rule of surviving an adventure.

Underground, Willett hears unnatural wailing. An immense passage stretches away, broken by regular archways. Willett begins exploring. He finds CDW’s library. Years’ worth of papers and notes go into his valise—but there’s nothing in CDW’s handwriting from the past two months. There’s plenty in Curwen’s hand, though. He finds no third handwriting that could be Allen’s.

He finds archaic symbols—the Dragon’s Head and Tail—and the words of the accompanying spells. He starts repeating them under his breath. As he continues searching, the wailing and stench increase. He finds a vast pillared space with an altar in the center and oddly pierced slabs in the floor. He shrinks from the altar’s horrible carvings.

Both stench and wailing are worst above the pierced slabs. He pries one loose. The moaning grows louder. Something leaps clumsily, frantically, in the well below. He looks more carefully and drops his torch, screaming.

The true horror of what he sees cannot be fully described. It looks like some of the altar carvings, but alive. It’s palpably unfinished.

He crawls toward the distant light, afraid of stumbling into the pit. The candles flicker, failing, and he runs. He reaches the library as the lamp starts to sputter. He refills it and begins to recover his senses.

Determined (and perhaps a little stupid), he continues. He finds Charles’s lab at last: chemistry equipment and a dissecting table. And coffins, like any good lab.

He finds stoppered jars labeled custodes and materia, both containing fine powder. He recalls one of the letters: “There was no Neede to keep the Guards in Shape and eat’g off their Heads.” It follows that these guards are out of shape, a nastier condition than health magazines usually admit.

The materia, then, are the best minds from all history, kept here at Curwen’s whim and tortured for knowledge.

Beyond a door smelling of the chemicals that were on CDW when he was captured, Willett finds a chamber full of torture devices. There are several of the stoppered jars, one open: the greenish dust poured into a shallow cup.

The walls are carved with a different version of the invocation Willett’s been repeating. And repeats again now, trying to reconcile the pronunciations.

We strongly recommend not doing this in a newly discovered magical lab.

There’s a cold wind, and the terrible smell rises, stronger. A thick cloud of greenish-black smoke boils out. A shape looms through the smoke.

Ward Sr. finds Willett the next day in the bungalow, unconscious but unharmed. His valise is empty. Waking, he staggers to the cellar and finds that the platform no longer opens. The planks cover only smooth concrete. He recalls nothing beyond the looming shape, but something must have brought him upstairs.

Ward Sr. finds Willett the next day in the bungalow, unconscious but unharmed. His valise is empty. Waking, he staggers to the cellar and finds that the platform no longer opens. The planks cover only smooth concrete. He recalls nothing beyond the looming shape, but something must have brought him upstairs.

Willett finds paper in his pocket, inscribed with medieval script. The two men puzzle out the Latin: “Curwen must be killed. The body must be dissolved in aqua fortis, nor must anything be retained.”

In shock, they go home. The detectives assigned to Allen call, promising their report the following day. The men are glad to hear from them; they believe Allen to be Curwen’s avatar.

They confront Charles. When Willett berates CDW for the Things left in pits for a month, unfed, CDW laughs mockingly. When Whipple went below during the raid, he was deafened from the sound of the battle and never noticed them—they haven’t been trapped for a month, but for 157 years!

Willett mentions the lab, and CDW says it’s fortunate that he didn’t know how to bring up what was in the cup. Willett wouldn’t have survived, for it was the dust of #118. CDW’s shocked to learn that #118 appeared and yet spared Willett. Willett shows him the message. CDW faints, and wakes muttering that he must tell Orne and Hutchinson.

Willett writes later for news of Orne and Hutchinson. Both have been killed—presumably by #118.

The detectives haven’t found Allen himself, but report that he has a scar over his eye, like Curwen and now CDW. His penmanship is identical to CDW’s recent writing. They’ve found his false beard and dark glasses. Ward and Willett realize no one’s seen Allen and CDW in the same place. A photograph of CDW, altered to add the disguise, is recognized as Allen.

Willett visits CDW’s home library, braving the noxious smell that now permeates it, and searches alone. He cries out and slams a cabinet, then demands wood for a fire. Black smoke emerges. Later, his servants hear him sneak out, and the paper again reports graveyard prowlers.

Willett writes to Ward Sr. He must not question further, but the matter is about to be resolved. Charles will escape the asylum, “safer than you can imagine,” but he won’t be restored to his family. In a year, they’ll erect a gravestone for a young man who never did evil.

Willett speaks with “Charles” one last time. The thing in the cabinet, now burned, was CDW’s body, and the man before him now is Curwen.

Curwen begins an invocation, but Willett interrupts, chanting the Dragon’s Tail. The words silence Curwen—and the man called up out of time falls back to a scattering of bluish-gray dust.

What’s Cyclopean: At last: “cyclopean vaulting” in the passageway below the bungalow. Alas for Lovecraft that he also gives 2 of 3 precise dimensions: 14 feet high by 12 feet wide. Even stretching into the unimaginable distance, cyclopean’s still smaller than expected.

The Degenerate Dutch: This segment focuses enough on the principal players to avoid racist slurs. We do get an extremely rude mention of T. S. Eliot.

Mythos Making: Yog-Sothoth is mentioned repeatedly. We also get far too specific details on the nasty spells to raise the dead and/or summon Things from ye Outside Spheres.

Libronomicon: Unless you count Eliot’s Wasteland, we just get letters and notes today.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Willett goes briefly mad on seeing the thing in the pit. He also continues to insist, for far too long, that he’s merely trying to understand a young man’s psychological case.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Whew! I feel Lovecraft doesn’t quite make the dismount here, not surprising in a work far longer than anything else he attempted. Willett, after showing remarkable genre savvy at first, persists far too long in assuming CDW is still what he appears, just a troubled young man. And the exploration of the Underdark caverns, though fascinating, regularly sinks into a miasma of foetid melodrama. I have great tolerance for Lovecraft’s language, but “he screamed and screamed and screamed” is not one of his better moments.

The idiot ball is in serious play—in Willett’s slowness at figuring out who’s in the asylum, in his insistence on solo subterranean exploration, and in his casual repetition of a chant from an eldritch tome. That this works out well for him is little excuse—he may be the only investigator in Mythos history to get so lucky.

On the other hand, the vanishing entrance to the Underdark caverns is effective and creepy. It supports earlier suggestions that this isn’t merely an underground complex undermining the Pawtuxet riverbank. Also creepy: #118 is still out there. Just because it didn’t like those who wanted to torture it, that doesn’t make it particularly benevolent towards modern humanity. Sequel, anyone?

We see here ideas that Lovecraft gets back to later, in very different form. Curwen and company’s mission is, with a bit of a squint, essentially the same as the Yith’s. Both seek to learn all they can of Earth’s esoteric history, and to speak with the greatest minds they can reach. They’ve learned how to cheat death and move from era to era. And like the Yith in Peaslee’s body, Curwen kind of sucks at passing. But aside from that one shared failure, Curwen’s friends aren’t nearly as good at what they do—they have a shorter reach than the Yith, and their methods attract significantly more attention. And they’re much worse hosts.

“Here lay the mortal relics of half the titan thinkers of all the ages.” Bet some of them spent time in the Archives, too, and liked it better. The Yith are really much nicer—not something one gets to say very often.

I keep waiting for a good place to talk about how Lovecraft handles mental illness and “madness.” Maybe this is it? Lovecraft’s own family history made him nervous of the subject, and he danced around and with it in pretty much every story he wrote. Not always with the greatest sensitivity, though I’d be hard pressed to name a topic that he did treat delicately—not the man’s strong suit.

Here we get actual attempts to diagnose mental illness, alongside the more poetically licensed gibbering. There’s much to forgive here, given that 20’s clinical psychology was… how do I put this delicately… damn near useless. People tried, but almost none of the era’s ideas about etiology or treatment have survived professionally into the modern era, and for good reason. (Caveat: I’m an experimental psychologist; I eagerly await correction or elaboration from those more intimately familiar with 20’s clinical practice.) So where modern writers have little excuse for vaguely described nervous breakdowns in response to Things Mortals Were Not Meant to Know, Lovecraft worked with what he had.

Sometimes when I’m being charitable I distinguish between Real Things and Poetic Things. Serpents are malevolent creatures that hiss and blink through the Harry Potter books, and snakes are what you find in the zoo. Likewise we have madness and mental illness.

But the more literary Madness still shapes how many people see mental illness. You can find in any newspaper the assumption that bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and narcissistic personality disorder (distinguished from one another only vaguely) all lead to violent, gibbering breakdowns. On the other tentacle, I know people who reclaim the “mad” label as a way of dealing with their own experiences of the world.

I’d love to see modern Mythos stories deconstruct this particular trope. People with autism who make great investigators because they process interactions with elder gods differently? People who come out of hidden nether realms with recognizable anxiety disorders? Reading suggestions very much welcome.

Anne’s Comments

This novel makes me wish Lovecraft had lived to write more long fiction. Given ample space, his gift for telling and provocative detail takes off. Writing about his beloved hometown contributes richness and authenticity along with the emotional resonance noted earlier. Compared to many shorter works, the prose verges on purple only where the omniscient narrator seems to sink into Dr. Willett’s shocked voice. Could length as well as generally distant narration lead to this restraint? Lovecraft isn’t dashing off an expressionistic sketch of the terrible here—he’s producing (for him) an epic painting, with Pre-Raphaelite attention to the minute.

For example, detail on the catacombs starts at the entrance, hidden under a washtub platform that pivots under the right pressure. (If I remember right, a similar mechanism opens the entrance into subterranean terror in “The Rats in the Walls.”) Catacomb rooms don’t have generic doors—they have the six-paneled models common to Colonial architecture. We get formulae, exactly as written out. We get the mystery script of what Willett summoned—8th century Saxon minuscules! “Things” aren’t kept in bland cages but in brick wells under pierced stone slabs, and “Saltes” don’t reside in plain old jars but in vessels of antique Greek design: lekythos and Phaleron jugs. Then there are those caches of clothing, Colonial and modern. The reader must wonder what they’re for. Willett supposes they’re meant to equip a large body of men. Or maybe not exactly men? Maybe the legions from underneath the wizards hope to “have up?” Maybe summoned guards and interviewees? You don’t return from the dead with your clothes intact, do you? Or maybe some antique clothing was worn by Curwen’s slaves and sailors who disappeared. Speaking of which, to build such an impressive lair, Curwen must have employed them as more than experimental subjects and/or “Thing” sustenance.

On a larger structural note, I like how Willett’s “raid” echoes Abraham Whipple’s. Whipple and his small army went well-armed, Willett alone with valise and flashlight—dude, once I heard that dull howling and slippery thudding, I’d have been out of there. Ironically, it’s Willett’s solo spying that brings Curwen down. Whipple and Co. made so much noise and fuss, they missed a lot of things. Er, Things.

A third article about nefarious doings in the North Burial Ground is a nice touch. The first incident in the cemetery—digging up Curwen—starts the horror. The second—Curwen vengefully excavating Weeden—deepens the devilry. The third—Willett burying Charles’s ashes—sets things as right as they can be set and returns the sacred ground to its rightful use.

Charles Dexter Ward, I find, is so packed with plot bunnies the hutch is exploding at the seams. My absolute favorite is #118. Who did Willett accidentally summon? Turns out it wasn’t who Curwen expected, a someone whose resurrection Willett wouldn’t have survived. Uh oh, those pesky switched headstones again. The 118 Curwen wanted was probably someone of his own sort, steeped in dark magic. Luckily for Willett, it was instead an enemy of dark wizards so potent that Curwen fainted at the sight of his missive and woke up babbling that Orne and Hutchinson had to be warned at once. Curwen was right to faint—within six months Orne’s house is wrecked and Hutchinson’s castle explodes.

Number 118 is no one to mess with, evil necromancers. I’m intrigued by the last of the penciled notes Willett finds in Curwen’s summoning chamber, presumably written during his previous interview: “F. soughte to wipe out all know’g howe to raise Those from Outside.” Could 118 be “F”?

“F” or no, if resurrection confers immortality or if he knows another way to extend life, 118 could still be around. I’m thinking he wouldn’t be able to put himself back down simply by reciting the descending formula—or Curwen couldn’t recite that formula without re-dustifying himself, right? It doesn’t seem the necromancer’s intention is necessary—Willett raises 118 inadvertently.

I say 118 walks among us, friends, keeping us safe from unrighteous magicians. And, because why waste a great lair, I say he at least occasionally resorts to the Pawtuxet catacombs he sealed off. Under concrete. So he’s also adept at masonry.

118, you rock. I’d still like to think Orne and Hutch escaped you, though, and that a sanitarium housekeeper swept up Curwen’s Saltes before they blew out the window. And kept them in a jar. Because hypnotic suggestion from that force bred in the outside spheres, that’s why.

Finally, the Things. In the brick wells so small they couldn’t even lie down, just squat and howl for all time, or at least 157 years as of 1928. I seriously feel so bad for them, unnamable and smelly as they are. My vote for most sympathetic monsters in the Lovecraft pantheon. I hope 118 sent them back wherever they came from, poor Things.

Next week we take on some shorter work with a Brief Deities theme—join us to learn more than man was meant to know about “Nyarlathotep” and “Azathoth.”

Image: Nice place for a bungalow. Photo by Anne M. Pillsworth.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

So, we end with, for once, something happening: a kind of dungeon crawl, at that.

I don’t really have a lot to add here. Lovecraft himself felt like the novel wasn’t very good. Whether he might have attempted more long works had he lived longer and then perhaps gone back and attempted to revise this is hard to say. He wrote this right after Dream-Quest and doesn’t seem to have attempted any other long works in the little over a decade he lived after this. There’s some good stuff here and he could have learned from some of the narrative techniques he tried out, but on the whole it just doesn’t work for me.

The identity of #118 is probably the biggest question. I don’t know if he offered any hints in his correspondence. If 118 and F are the same person, then our only other clue is someone who would write in 8th century Saxon script

(which I think would have been uncial not miniscule; I think the first miniscule was Carolingian). Without the script clue, my guess would have been perhaps Nicolas Flamel, who had a reputation as a good (as in not evil) alchemist. Must be somebody pretty powerful to scare Curwen so.I don’t know of any post-Lovecraft authors who took a more modern approach to insanity and the Mythos. Back when I played Call of Cthulhu, we usually tried to connect the insanity with whatever it was that finally pushed an investigator over the edge. I would think that a lot of people who appropriate “mad” these days are drawing on things like Girl Genius or Narbonic. It probably plays well with steampunk.

ETA: Correcting my paleography. Miniscules did arise earlier.

I remember, when I first read this novella as a teenager, the identity of 118 bugged the heck out of me. I vaguely assumed it might be Merlin; the time frame fits, although Merlin’s inclusion/chronology in the Arthurian legends is nothing if not inconsistent.

I hadn’t associated 118 with “F.” If that’s the case, I refer to Sharon Turner’s 1828 work The History of the Anglo-Saxons from the Earliest Period to the Norman Conquest (Volume I) where she says of the 8th century Saxons, “Hama, Flinnus, Siba, and Zernebogus, or the black, malevolent, ill-omened deity, are said to have occupied part of [the Saxon’s] superstitions” (221, italics mine). This seems awfully esoteric, but then Lovecraft was all about the esoteric and the publication date means he could have read this work.

(Note: I would love to say I “just knew” this, but I can’t. Google is my friend. :P )

Whoops – the posting mechanism ate part of my post. The full quote should read: “Hama, Flinnus, Siba, and Zernebogus, or the black, malevolent, ill-omened deity, are said to have occupied part of (the Saxon’s) superstitions.” D’oh!

I’m intrigued by the last of the penciled notes Willett finds in

Curwen’s summoning chamber, presumably written during his previous

interview: “F. soughte to wipe out all know’g howe to raise Those from

Outside.” Could 118 be “F”?

The avenging immortal F. may well be the same as B.F., mentioned earlier, and assumed to be Benjamin Franklin.

Which is AWESOME and therefore correct. (“Too beautiful not to be true” as Einstein or someone said.)

I agree that Lovecraft’s followers continue to approach and use mental illness with an insensitivity unforgivable in today’s world. I disapprove of the supposedly-humorous “Insanity Certificates” sold by the HPL Historic Society, and the casual way in which the fandom throws around words like “madness” and “insanity.”

@3

That’s interesting. The first thing that jumps out at me is, of course, Zernebogus, who is obviously best known from American Gods as Chernobog. A bit of poking around in Google books turned up a German text that mentions Flinnus as a god worshipped near Leipzig with a terrrible form. He wore a long coat and carried a burning staff. Hama and Siba are tougher. “Black, malevolent, ill-omened deity” certainly seems to refer to Chernobog, could it refer to all four as the same god with different names? And that description could also fit Nyarlathotep, but I don’t know why he would want to “wipe out all know’g howe to raise Those from Outside.” Seems rather counter to his brief.

It’s interesting to seek a conceptually plausible means to explain how

Curwen’s adversary, the more powerful entity called up in the providential

accident by Willett, manages to make Curwen’s huge underground laboratory

quietly vanish, like the disappearing cavern in “The Transition of Juan

Romero.” No explosion, no cave-in, no mess: “Underneath [the torn-up floor

planks] the smooth concrete was still visible, but of any opening or perforation there was no longer a trace.” Presumably no one had gotten a remodeling crew in to refurbish the basement. Could that cryptic entity have shifted events to a parallel universe in which everything else is the same, but Curwen’s lab had never been?

Regarding the 12′ x 14′ “Cyclopean vault” here: I believe that Cyclopean

refers to the size of the stones in the masonry, not the dimensions of the

structure.

Jaime Chris Weida @@@@@ 3 & 4 With your Google acumen, you have earned entry into the Miskatonic University Arcane Archives for the next year. Just mention my name to Mrs. Wolff, the chief librarian. Or better yet, mention Flinnus! a1ay @@@@@ 5 I think Ben Franklin would get along pretty well with necromancers, actually. AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 6 My friends in health care have great fun pointing out the medical errors in fiction of all genres. Psychiatry does little better than, oh, oncology. Like Ruthanna, I’d like to see some stories that address, with authority earned or borrowed, the mental illnesses that Mythos exposure might really cause. Anxiety, for sure. Depression over the realization that the truth is not only out there, it’s WAY WAY WAY out there? And the idea of autistic researchers who relate differently to Mythos creatures? Love it.

I think Lovecraft underestimates how difficult it would be to cremate a human body in a domestic fireplace. (This made me less sure about what was going on, on my first reading, than I might have been.)

Speaking of the body: that’s really a weak link in Curwen’s scheme to replace Ward. Surely a corpse hidden behind panelling in an inhabited house is almost certain to be discovered, as it starts to decompose? He was desperate, I suppose, & couldn’t find a better way to dispose of it, but if I were him I’d have spent every day after that terrified that it could have been found. (Possibly he hoped the body would be unidentifiable by the time it came to light, not being familiar with modern forensic techniques, but Ward would then be a prime suspect…)

@2

I’d call At the Mountains of Madness a long work. It’s about 80% of the length of TCoCDW or 95% of TDQoUK (and often covers more pages than the latter, due to the chapter breaks).

a1ay @@@@@ 5: I want to believe–that would be awesome–but they call him BF awfully consistently, and seem to find him more desirable than terrifying. So far I’m most persuaded by DemetriosX’s suggestion of Flamel, on a purely logical level. But then again, the Einsteinian proof for Franklin is pretty compelling.

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 6: Yeah, there’s this whole dialogue waiting to happen that just hasn’t yet–I think, in part, because in this respect Lovecraft really was a product of his time. And society hasn’t advanced as far on mental illness as on race, so it doesn’t stand out for as many readers.

I’m presently attempting a Lovecraftian story with a protag who has an anxiety disorder. And discovering that it makes it *really* hard to get the mood right, as she’s prone to worrying about the mundane stuff in a way that kind of drowns out the signal from the eldritch bits. I am fine tuning, but thinking thinky thoughts about what kind of narrative personalities and attitudes are compatible with cosmic horror. No definite conclusions yet, though it may be related to why it’s hard to put Sherlock Holmes and Cthulhu in the same universe.

DGDavis @@@@@ 8: My interpretation was that the caverns always extended in an… unusual direction, and the only thing needed to make them “disappear” was to break the existing spell that kept them accessible.

Ngogam @@@@@ 10: My first thought was that Curwen had already started the “salting” process, so the body was more brittle and easier to burn. But that leaves an even bigger gaping plot hole, doesn’t it? Curwen is the world’s foremost expert in reducing dead bodies to an anonymous and portable form! And given his great need to learn about the modern world, wouldn’t he want to have his heir available for questioning? He’s got no excuse to leave that body lying around!

Yeah, Curwen should definitely have gone back for Charles’s body some dark night, so he could reduce the poor boy to saltes for future reference.

As for the catacombs by the Pawtuxet River, alas, I fear that Lovecraft simply wanted an underground lair, so he put ’em there, engineering problems be damned. If I were Curwen, I would have just kept my saltes in a nice dry warehouse, labelled as spices from his East India trade, just in case anyone got curious. In the twenties, he could have upgraded to a bigger warehouse on the Providence waterfront.

As for performing blasphemous rites and conducting unholy interviews, alas. Hutchinson had by far the best set-up for that in his Transylvanian castle, under which catacombs would have been a natural enough phenomenon.

I have always loved the denouement here, simply because Lovecraft demonstrates knowledge of a principal generally unknown to contemporary grimdark writers: if the universe really is completely uncaring, if things in it really do happen according to random chance, if the gods are blind intelligences who care not for humanity and do not influence fate, if fate itself is a meaningless concept… then every so often random chance will cause the good guys to win. Not often. Certainly not often in Lovecraft’s world in which so many things are dangerous.

But, once in the entire body of Lovecraft’s fiction, the heroes rolled the dice and it came up ‘you win everything’. I love this example of his commitment to his own metaphysics. A lot of current grimdark takes place in universes which are represented as neutral, but which are demonstrably actively malign. Taken as a story on its own, being saved by a mislabeled urn full of essential salts does not entirely feel earned, but in Lovecraft’s corpus as a whole I think it is both earned and necessary.

The statement of Curwen’s about the monsters having been imprisoned for a hundred and fifty years is one of the two or three bits in Lovecraft I always find genuinely creepy, too. TCoCDW has huge, gaping, ridiculous flaws, but those two things about it mean that I do respect it, and don’t think it is as bad as HPL himself thought it.

Why didn’t he close the lid over the creature again if he is afraid of it?

Maybe the underground tunnels are some kind of fairy realm and the gate to the real world closed.

I thought the hidden body was some kind of saltes and not a normal corpse.

The Dragon’s Head ? and Dragon’s Tail ? are astrological symbols for the places where the moon crosses the ecliptic.

The part about next week’s chapter was confusing. I am new to Lovecraft and was looking for a story Brief Deities. I did figure out that there are two stories Nyarlathotep and Azathoth instead. You always link to this week’s story. If you link to next week’s, too, it would be clear what is meant.

@13: Formerly, I thought that the term Grimdark was for fiction that was so deliberately over-the-top (like Mary Gentle’s Grunts) that it parodied attempts at “serious” fantasy. To this day, I’m not sure why people take it seriously… Yes, it’s nice that the good guys get a token victory.

ETA: <spoiler> the heroes (well, sort-of) win in Cast a Deadly Spell for reasons equally arbitrary.</spoiler>

Rush-That-Speaks @@@@@ 13 Good point — if good is Heads and evil Tails (Dragon’s Head and Tails?), you should roll good half the time. Of course, the Outer Gods don’t actually play with 2-sided dice — they prefer all-consonants Scrabble.

@16: The Outer Gods roll tesseracts in their crooked houses.

SchuylerH (@17): So, you are saying that instead of d4’s, they use 4d’s? Bet the probabilities add to to more than 100%, too.

I have also always assumed that #118 must be Merlin. Powerful Medieval wizard and so on. Also a bit ambigious, which could explain why Curwen was surprised that Willett surprised him.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 17: Well, they WOULD roll tesseracts in their crooked houses, except every time they do, the Hounds of Tindalos try to eat them, choke, and have to be taken to the vet. Do you know what a good interdimensional vet costs these days?

One should only roll tessies in curved houses.

I just read and enjoyed the short story “Remnants,” in the excellent Lovecraft’s Monsters anthology, which centered on an autistic girl in a world conquered by Old Ones.

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 21: Ask, and we shall receive!

RushThatSpeaks @@@@@ 13: Agreed. Not only does it better fit a truly

uncaring universe, but it tempts one to actually care what happens to

the characters–since it’s just possible that they’ll be okay.

AeronaGreenjoy @@@@@ 21: Cool, that anthology was already on my wishlist and has just moved up!

Everyone @@@@@ everywhere: There is something wrong with all of you. I did not need to think about the Outer Gods role-playing. Or how much that may explain about some of my GMs in college.

Just to clarify: #118 is Rincewind, obviously.

Currently, I have a sort-of theory that #118 was a member of the Knights Templar. I don’t know why, it just kind of seems to fit. The ultimate holy warrior, links to witchcraft, that kind of thing. And when I asked myself who I would fear, alive or dead, if I was an evil necromancer, it was the first thing that popped into my head.

Not Merlin, he was Celtic not Saxon, and the Knights Templar wouldn’t be along for another five hundred years give or take.

This autistic is currently writing Lovecraft-inspired fiction featuring autistic protagonists who are indeed able to view the Elder Horrors differently because of their different outlook and sensory processing.

Martin @@@@@ 27: That sounds awesome; I look forward to it!

Has this turned up anywhere in the Reread discussion threads yet? BBC did a 10-part adaptation of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward in podcast form; they moved it to modern times and did it in the form of a true-crime podcast.

http://www.sweettalkproductions.co.uk/production/charles-dexter-ward/

I’ve only listened to the first 3 or 4 episodes (30 minutes each) but it seems quite good so far.

I always took “No. 118”, which the story heavily implies to be mislabeled, to be none other than Lovecraft leaping into his own story—of which he was thoroughly sick and tired by his own admission—to provide a hasty and pat resolution, though I couldn’t give you a shred of textual evidence to back that up. Just a feeling…